Living in Singapore over the past decade, I’ve had first-hand experience of the intense yet oftentimes transient nature of expat friendships.

Moving from London to South East Asia to start a family 10 yeas ago, I had to make a real effort to meet people for the first time in my life. The wide range of women I met in Singapore led to me protagonists who I was convinced would never have been friends in another environment.

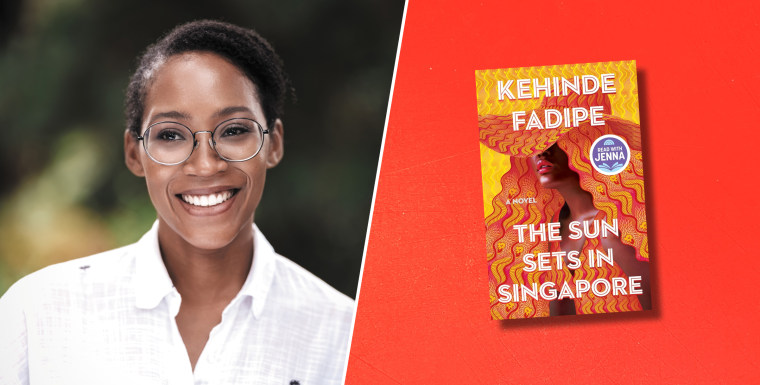

My book centers on Dara, a British-Nigerian lawyer who has invested everything into making partner; Amaka, a banker who uses a shopping addiction to run from the stress of her family strife; and Lillian, a Nigerian-American pianist whose marriage is falling apart.

Thrown into the mix are their Singaporean and English colleagues, a Thai-born Indian boyfriend and the wider African diaspora including a group of women in a book club. These expats navigate the melting pot of Singapore’s Malay, Chinese and Indian heritage, with some escapism and luxury travel thrown in.

My first year in Singapore brought an initial wave friendships, loose connections in the form of young, working women who saw Singapore as the perfect playground for their 20s. Sometimes they were friends of old school friends or distant relatives of pre-existing connections; many times, they were simply someone who had heard I was “looking for a friend."

I, who had previously viewed small talk as anathema, now had to swallow my pride and accept offers of companionship from girls I had little in common with. It was a decision that paid off.

No matter the day of the week, these women had so much energy and never turned down the possibility of a night out. They worked long, hard hours as executive assistants, or in marketing, communications or public relations where they enjoyed insane discounts from fashion brands and free tickets to events like Formula One, and they partied as often as they exercised. They were always on the guest lists at the best nightclubs (most of which are now closed) and they knew all the best spots for one-for-one drinks on Wednesday’s Ladies Night.

Like my character Amaka, a banker torn between two men, these women had complicated and entertaining love lives, and there was invariably a boyfriend overseas somewhere. Within a year of meeting most of them, they had gotten engaged and left Singapore, moving to Hong Kong, Thailand or back to Europe, and the friendships, which were short but bright, fizzled out.

While I suddenly had more time on my hands, it became clear to me that the fear of having deep connections severed by the transiency of expat life had led to me making superficial friendships. I decided that I would rather befriend people who I had an authentic connection with, even if they left six months later. Friendship, if it is true, I reasoned, should be able to survive time and distance. Avoiding the pain of the loss was not a healthy way to live.

I was more intentional from this point onwards and so, the second wave brought women into my life with a foundation of shared hobbies and interests.

Websites like Meetup.com are popular with expats in Asia because when you live abroad, you don’t have the luxury of lifelong, childhood buddies with whom to bond. Plus, with long working hours, it’s extremely convenient to be able to select from specific organized activities such as language learning, outdoor exercise and sports, movie clubs and of course, book clubs — one of which centers heavily in “The Sun Sets In Singapore.”

Friendship, if it is true, I reasoned, should be able to survive time and distance. Avoiding the pain of the loss was not a healthy way to live.

The beauty of meeting people this way is that you get drawn into other groups and you go to parts of the city that you wouldn’t normally. As I spent consistent amounts of time with women in my writing, netball and early morning yoga groups, our ties deepened. We shared more about our lives and families, and through meeting our other friends and partners, we created a little community.

My life began to change with the birth of one and then two babies, and with it came both a need for close friends who understood the huge transition from independence to the messy and oftentimes overwhelming powerlessness of motherhood.

As a young mother, the pace of life slowed down and Ladies Nights were replaced with La Leche nursing group meetings, held in homes where the most disgusting gluten-free, sugar-free and dairy-free ‘treats’ were the only snacks available. All interactions took place cross-legged on the floor, or on all fours if toddlers were in their crawling phase, and it was the norm for conversations to break off in order to sign “poop,” “pee” and “thank you” to the babies with us.

We no longer frequented rooftop bars or sushi lunch spots, but instead organized our lives around information found in articles like “43 Awesome Things To Do with Children this Weekend” and “Why Co-sleeping Boosts Your Baby’s Brain Power.” The determining factor in choosing any cafe to meet a friend was the existence of clean changing tables, free toys and a playpen and mat; that there were so many to choose from in Singapore was greatly relished.

There were many great things about these expat mummy groups. They were a treasure trove of information where you could find out how much rent everyone else was paying, where to get antibiotic-free meat without burning through your budget, whether it was too soon to register your kid for Mandarin lessons (it was never too soon) and the myriad of ways you could use coconut milk.

More crucially, these groups became spaces to safely voice the guilty, secret fears many expat women share about leaving their careers to live in a country as dependents, spouses and children who are “attached” to the main breadwinner and without whom they would not be able to remain.

How was it possible, after years of the feminist movement, that our lives had become identical to our mothers and grandmothers? Once spoken, these fears would be reeled back and tucked away, like the leftover banana bread and chia seed puddings in take-away boxes we carried with our strollers and car seats.

Once I started teaching, my friendships became more balanced, a healthy line between colleagues, acquaintances and true confidantes was drawn. Like my character Lillian, an American pianist who has left her career to be a housewife, I taught in a language school and then in international schools, work took center stage where more natural friendships were forged in daily working life, and added to connections that have lasted through the years. I also began to make more Singaporean friends, mainly through my church, and befriended more parents of my children’s friends.

One of my favorite passages to write in “The Sun Sets In Singapore” was a scene in a barbecue in which Dara, an ambitious lawyer who gets drawn into a workplace rivalry, describes the incongruous blend of guests gathered. This mix of people is the most fascinating aspect of expat life in Singapore to me, and why I enjoyed writing from the perspectives of three very different characters who discover when their marriage falls apart, their job is on the line and their shopping addiction has spiraled out of control, that the strongest and most precious friends are the ones who show up for you.

As close friends began to leave for Europe and the States pre- and post-COVID, I began to appreciate the type of bond that develops with people who have once shared and witnessed seismic and oftentimes painful shifts in each other’s lives. My connections also deepened with the friends I had left back home a decade ago, and I began to appreciate and value them as much as the friends I have in Singapore.

Far away from my blood relatives, my friends have become like family. They are women who celebrate my achievements and who care as much about my struggles as their own. We have, in some way or other, opened up about the true reality of our lives. And most especially, in times of crisis, we have shown up.