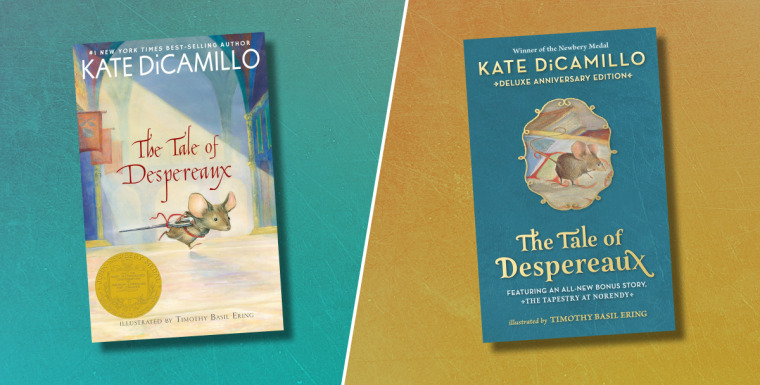

Kate DiCamillo, the beloved author behind children's classics like "Because of Winn-Dixie," is celebrating the 20th anniversary of her Newbery Medal-winning book "The Tale of Despereaux."

Revisiting Despereaux, the namesake big-eared mouse who travels into the dungeon of a castle to save his beloved princess, leaves DiCamillo visibly emotional, especially when she recalls how the book has impacted her readers over the past 20 years.

DiCamillo starts tearing up when I tell her I read “The Tale of Despereaux” when I was in elementary school, likely just a few years after it was published in 2003, and that it was one of the books that made me a reader.

“To be faced with an adult and to think about it, makes me cry a little bit. The kid — you know, you — connecting with that book,” she says through a smile. “It’s just the biggest deal in the world to me, so thank you. It’s a wonderful gift. Huge honor.”

In honor of the book's 20th birthday, DiCamillo answers questions about its origin story, including why she was afraid to write the book, what's in the works for her in the future ... and if there will ever be a sequel for more adventures with Despereaux.

Can you take us back to the moment that you got the idea for "The Tale of Despereaux?"

I had written "Because of Winn-Dixie," and it was a book that did better than anybody thought it would do. It was a wonderful, amazing thing for me as a writer. What I kept on thinking was, "I need to write another book like that, so that people will keep on loving me," which is a terrible reason to write a book.

I was stuck and spinning my wheels a little bit, trying to do another "Winn-Dixie." I went to visit my best friend — she was living in St. Louis at the time. Her son was 8 years old and a big reader. He had never been impressed with me before, but all of a sudden there I was with my name on a book and that really impressed him.

The whole visit he followed me everywhere I went, and then right before I left, he asked if he could have a word with me in his room. So we went into his room and he said, "I've got an excellent idea for a story." And I said, "What is it?" He said, "It's the story of an unlikely hero with exceptionally large ears." I was like, "Wow, what what happens to the hero?" And he said, "I don't know. That's why I want you to write the book."

That was the very beginning. I loved the phrase — I don't know where he got it from — "unlikely hero." He didn't say a mouse, but a mouse to me seems like the most unlikely hero. Pretty soon after that conversation, I started on "Despereaux."

How did you pick out the characters' names?

Despereaux's name was the very first name, and I don't speak French. And I was like, Does that actually mean despair? It was just in the beginning of when you could Google things. I woke up in a cold sweat in the middle of the night and Googled the word "despereaux" to see where I had unwittingly taken it from, and nothing came up. So it was like, "OK, then my brain made it up. That's OK."

For me, everything about writing is hard, except for the names. They just show up. They pop into my head. I've learned to pay attention to them and write them down. But I don't know where they come from. And I still Google them when something strange shows up.

Were there other inspirations for this story?

The big thing for me with this story was that intrusive narrator. I remember the New York Times review said it was like the loudest voice at a cocktail party. When I was writing this book, I was really afraid because I was going in a totally different direction than "Winn-Dixie." And I thought, "Oh no, no one's gonna read this or like it." It was a much more complicated plot than anything that I'd worked with before.

As I sat there weeping quietly at the computer each morning, this voice showed up — that narrator's voice — and it sounded like it knew what was going to happen in the story. What I did, instead of knowing myself, I just attached myself to that voice, and let that smart aleck-y, know-it-all, but warm voice lead me through the story, the same way it was leading the reader through the story. For me, it's a book about being afraid and doing something anyway, which is very much what Despereaux does when he goes down into the dungeon.

You said you were afraid to write "Despereaux" after "Winn-Dixie." What did you tell yourself to get behind this story?

What did I tell myself? It's a wonderful question and no one has ever asked me that before. I remember I had a little necklace — I don't know what happened to it. It was just a dog tag and it had the word "courage" on it. When I came down to write every morning, I just kept on thinking the only way out of this is through it. I have to, I cannot leave this mouse with his fate unsettled. I mean, it sounds ridiculous, but I felt like Despereaux was real and he was being brave and I had to be brave with him. I never ever thought, 'Wow, this is really working." Instead I thought, "I really have to tell this."

I felt like Despereaux was real and he was being brave and I had to be brave with him.

I felt like Despereaux was real and he was being brave and I had to be brave with him.

Kate Dicamillo

What has it been like revisiting this time in your life, 20 years after "Despereaux" was published?

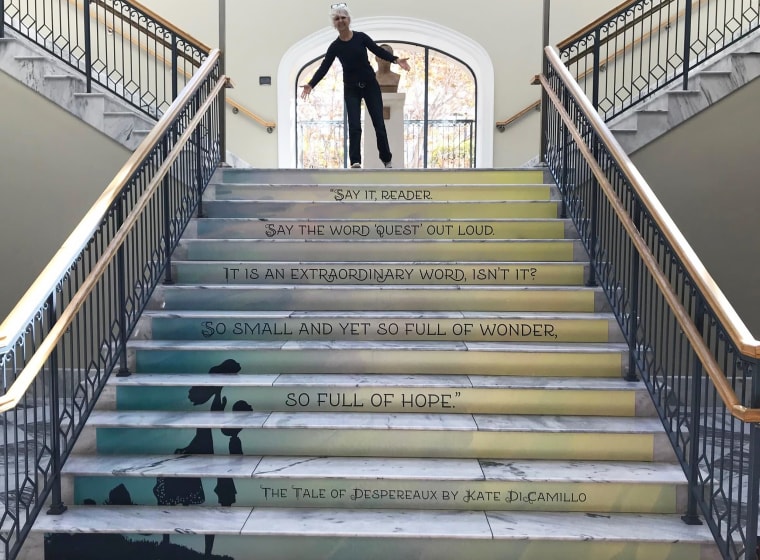

It has been a deeply moving experience because of readers like you who are grown up. I've heard from adults, who as kids, were in the hospital: "This was the book that I read again and again and again and again because it convinced me that I could be brave." It's astonishing to me.

I always think about something my best friend said to me when I get overwhelmed with people saying things like that. She always says, "It's not about you, pumpkin." And it's not about me — it's about the incredible power of story, and how stories can make us feel seen and less alone and how it can connect us to each other.

What is it about your books that you think leaves such a lasting impact on readers?

The first image that popped into my head — and I hopefully I can do this without crying — I was in North Carolina in a theater. I don't know how long ago it was. And during the question and answer session, a little boy stood up. He was probably nine years old. He held up "Despereaux." He said, "I have dyslexia. This is the first book that I read on my own. I wanted to know if you wrote it for kids like me?"

Wow, I had to bend over before I could answer him. I said, "I wrote that book from a deeply afraid place, from my own brokenhearted place. And then it reached out and connected with you. And so yes, I wrote it for you. I wrote it for all of us, for people who are brokenhearted and looking for connection, and so maybe it's that? I don't know." There, I got through it mostly without crying too much.

Tell us more about why you needed to include the images of cauliflower ears and soup in this book.

Poor Miggory, it's that thing that has bothered me since I was a kid ... of not understanding, often, the pain that other people around you carry, and how broken their hearts are and how easy it is to look past them. And so those ears make it hard to look past Miggory and her suffering and that empathy that we learn from books. Those cauliflower ears help with that. So it was not a calculated move.

Soup, much like toast, has the same meaning to me: Somebody is taking care of you. Soup, when I say the word, is you coming home from school on a cold afternoon. Somebody's waiting for you and they put a bowl of soup in front of you to take care of you. It's it's a way to take care of somebody — it promises something, soup does.

Would you ever write a sequel?

I doubt very much that I would, but if the last 20 years has taught me anything, it is that anything is possible. So I will not say no. I just will say it seems unlikely ... but anything could happen.

How do you keep in touch with your childlike self?

That is not a hard job for me at all. I remember hearing a Beverly Cleary interview and she talked about how that that 9-year-old in her was just like, right there. And that's just the way it is for me. There's nothing that I have to do to access that kid, that kid is always there — that's how I walk through the world. And boy, it's been a gift.

What are you working on now?

I'm working on working on fairy tales. It just seems like a time for fairy tales and Despereaux is a fairy tale. That's what the 8-year-old me is working on. Something that makes the world calm, right?

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.